For generations, the paan and Paandaan were used with great manners, which were referred to as Adab-e-Paandaan. “As Hyderabadis, we are foregoing our cultural evolution”, said cultural curator Dr Haseeb Jafferi”. A descendant of the fourth Nizam of Hyderabad, Salabath Jung, Jafferi, 32, will be speaking at the upcoming Hyderabad Literary Festival on ‘Adab-e-Paandaan’, or, the manners of the centuries-old habit of chewing paan.

“The Paandaan was the principal metaphor for the culture of Hyderabad. Sadly, these days the name of the city brings to mind only Biryani or Irani chai, none of which were traditionally associated with the culture of the city, whereas the Paandaan was. For generations, the paan and Paandaan were used with great manners, which were referred to as Adab-e-Paandaan. It was a sign of cultural literacy in people. Today, the paan has become a metaphor for dirtying the streets, which is in complete contrast with the origin and evolution of the paan,” Jafferi explained to Telangana Today.

Nawab Salar Jung Bahadur used to ask for paan to be served to his guests as a sign that it was time for them to leave, said Jafferi.

The paan would be presented to guests in a Nagardaan, a special tray covered with tor-e-posh, a silk or velvet cloth, with intricate design work on both items.

On the other hand, it’s a hot summer afternoon and the narrow streets of Jahanuma Lancer in the old city are quiet and deserted. In a tiny room in the locality that once was home to the army of Paigah Royals, 55-year-old Syed Siddiq Ali is busy polishing metal boxes of various shapes and sizes.

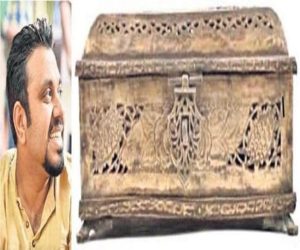

One after the other, Siddiq takes the box and rubs polish on it. “This is paandaan (metal box to store betel leaves). After several days I got an order from a wholesale trader as the season of Muslim marriages will begin soon after the month of Ramzan,” he says.

In fact, a complete paandaan set comprising a paandaan – a metal box with space to keep paan, supari (betelnut) and other ingredients that go into the making of a paan; nagardaan (a heart-shaped box in which a paan in placed), supari dabba (betelnut box) and ugaldaan (a receptacle for spitting).

“Buyers for the articles have dwindled over the years. In marriages, people are gifting some other articles to their daughters instead of the traditional ones as nowadays fewer women, with even some elderly persons, giving up the habit of chewing paan,” says Siddiq. A few families who still possess the paandaan sets bring out these during festivals or marriages and get them repaired or polished, he reveals.

Making the paandan set is a big task and takes around six to eight days. The first step involves cutting the brass metal sheet and then giving it the desired shape of the container. Next, they polish it and later assemble it. “People in four different workshops take up the job. Every set requires skilled men to do it,” says Siddiq who along with his family makes paandan sets. He also makes attar dan (attar box) and surme dani.

Only during the month of Ramzan there are regular sales of attar box. “Otherwise, we get orders only for marriages from the districts of Telangana, Karnataka and Maharashtra,” he points out.

With the orders coming down and drop in regular work, not many youngsters are taking to the craft. “The last decade has brought about a lot of changes. People are not seriously hooked to traditions and due to this, several crafts associated with the traditions of yore are passing through a bad time. With hardly any earnings left in the trade, we ourselves are not encouraging our children to take up it as a full-time work. After a few years we may not find any work,” laments Siddiq. #KhabarLive