Exploring the defunct mines and colonial charm. That gild the Kolar Gold Fields, where time and progress both stand still, #KhabarLive attempts to touch the new gold in the old mines.

The vague memories of the Kolar Gold Fields (#KGF) from readings in school. Illusions of grandeur always popped up in discussions about it, with KGF’s gold touted as some of the finest at the time. Thinking that it was just another name for the city and district of Kolar in Karnataka, #KhabarLive planned a day trip to KGF to explore the town better. If required, his background in mechanical engineering would help me get a crisper understanding of the science behind mining.

As #KhabarLive got off the highway onto the road to KGF, time seemed to slow down, the hilly landscape changing to arid plains. Before exploring the Robertsonpet market, we were in dire need of some filter kaapi. A cup at Hotel Janardhan—possibly the only decent restaurant in town—really hit the spot, rejuvenating us before we headed out.

Once a thriving shopping hub for English memsahibs and the miner families in town, the market is laid out as a grid, with narrow lanes designated for different goods. The bazaar was still walking up as we walked through, its smells—from spices, to fruits, to meats—a serious test of our olfactory senses. In the past, it’s said that you could buy all the ingredients required for a multiple-course European meal here.

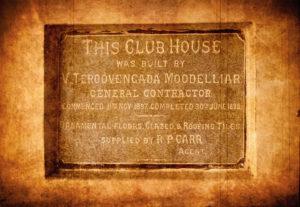

The facility is now called the KGF Cosmopolitan Club—it did explain the perplexed shopkeepers in the market, when we asked for directions. Upon a bit of cajoling and coaxing, the deputy manager allowed us a look into the club’s vintage billiards room, which lay tucked away in a rear corner of the building. The vintage cues with their ‘Miraka M1 Made in England’ insignia, the lovely raised spectator seating, and the wooden scoreboard were arresting antiques.

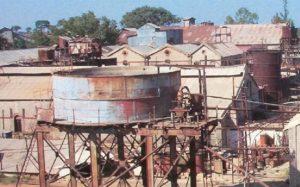

Situated a few kilometres away from the main town is the mining side, where one feels transported to the early 20th century. It was a time when thousands of locals worked in shifts at the mines, while the British officers lived a lavish life in comfortable bungalows.

The place evoked a good amount of nostalgia as we read the names of the club presidents and gazed at the vintage photographs in every room. A large grand piano adorns one of the halls, which, we were told, was a ballroom where Europeans used to dance the night away. Everything, including the guard’s memory, seemed to have gathered a lot of dust.

A few paces away was the bungalow of the erstwhile chairman of Mysore Mining company, where now the union president resides. The enviable Victorian property is built on several acres and has a little garden, a porch and a backyard.

A framed photograph of Ambedkar, a worker’s union identity card, a communist party membership card and a good old Atlas cycle were his assets in the tiny room. While I was eager to know his story, my father-in-law questioned him about the quantity of equipment. Ironically, a town that was built on its large employment opportunities, is now a place where jobs are hard to come by.

On the way back, stopped to look at relics such as the New Imperial Bakery and Victory Confectionery Stores—once a favourite amongst Anglo Indian residents, it stood opposite a hospital, and children would often be bribed with its sweet offerings. The beautifully vintage Champion Reefs post office, the Workshop, Our Lady of Victory Church, the football ground, the dairy and the St Joseph’s Convent were other quaint sights. The KGF Hospital, renamed the Bharath Gold Mines Ltd Hospital and once known for eminent doctors, is now an abandoned building. Another surviving group of relics are the vault-like structures which used to hold prisoners of war. They later came to be used as police quarters.

The prosperity of the early 20th century also led to the construction of a reservoir that supplied the mining town. Built in Bethamangala, about 13 kilometres away from KGF, it cost `11 lakh in 1903. The waterworks and the adjacent garden seem to have not changed much since then. The antique filtering units (which we suspected were past the point of effectiveness)and pumps, the dilapidated emergency telephone booth, the winding staircase, the huge collection tanks, and the electrical control unit with the insignia of the Mysuru Wodeyars can still firmly stake a claim amongst India’s industrial heritage.

The transformation of KGF from ‘Little England’ to a ghost town in less than a century is remarkable. While the descendants of the British visit to see remnants of the glorious town built by their forefathers, the Anglo Indians look back at KGF with the nostalgia of playing a role in creating its unique culture. But for the mining workers, who now have a daily commute to Bengaluru for work, recalling fond memories remains a difficult task.