It took 8 months for Uday Chauhan, ever since he set foot in a tribal hamlet, to convince 5 teenage boys and 2 girls to act in his educational movie.

It took eight months for the debutant director, ever since he set foot in a tribal hamlet in the state in January 2019, to convince five teenage boys and two girls to act in his movie. But that was not the tough part. The issue was that this movie was entirely based on sex education. The feature film, ‘Season of Innocence’, is based on the life of a 13-year-old boy and his journey through adolescence, puberty and sexuality.

The initial few weeks involved just gathering the boys together for a talk. None of the boys believed Uday when he told them that he wanted to make a movie in the village, he says.

The director says that getting the children on board with the film was a challenge. Uday first wanted to get them to trust him before he made the revelation.

“I took them in my car to a nearby tea stall, it was their first time sitting in one. They were all so excited and called friends on the streets to show they were in a car. That’s when I told them the topic of the film. There was pin-drop silence. Their cheerfulness had gone. They said — the film is fine, but the topic is bad. Why should we make such a movie?” he says.

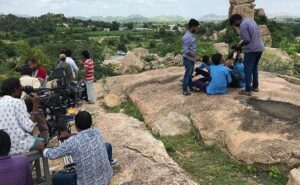

The film was shot in Mahabubnagar district’s Rajunaik Thanda, which has a population of 300 people and is Uday’s native. It took six weeks to only counsel them about the topic, educate them, and another five weeks to teach them how to act and be natural on camera – so, I conducted a workshop for months, he says.

“The reason I chose non-actors was that my target audience was mostly people from rural backgrounds — I wanted it to be raw so that they can relate to it as much as possible. This is why I spent time identifying ‘regular’ boys and casting them,” he says.

Uday’s idea of the movie also comes from his tour to several schools in rural South India, where he learnt that chapters on the reproductive system were being skipped in schools. Students were often asked to read it themselves and access to phones gave them an easy way to watch porn. In some instances, girls and boys of the same class were made to sit separately when being taught the chapter.

In Uday’s workshop, he also counselled the boys about good and bad touch, different forms of sexuality, how other genders needs to be respected and not objectified, consent, etc.

“I had to start with teaching them their school chapter on reproductive systems. It’s not just about body parts but tuning their minds and teaching them things that were important. I did not know if the movie would materialise, what size would it be – but I at least wanted these boys to learn something,” he says.

Uday points out how girls, when they attain puberty, are told about it, although not in the best way and with a lot of stigma around it. But boys do not have any channel of communication, not even the bare minimum. “Which is why I focused the story more on boys. The movie involves boys exploring porn, being bullied for not being masculine enough when they attain puberty and the pressure of being physically sexually active,” he says.

“No one at my home talked about all this before, and not even at school. We were very shy initially and thought — why to get involved in all this. But, after spending some weeks with him, we understood it better. I acted in the movie because I felt it would bring a good name to my village and my family,” Raghu says.

Objection from parents

Needless to say, the struggle was not just educating the boys and convincing them to be part of the project, there were many objections from the parents, village heads and others.

“When the word spread, the parents objected saying their kids’ future would be ruined and they would never be able to settle down. The village heads objected saying it would tarnish the image of their hamlet. Parents were told by people of the village not to allow their sons to do this,” he says.

Among the five child actors, one of the boy’s parents were construction workers in Mumbai, so he stayed alone in the village, cooked for himself and went to school. Another was an auto-driver’s son, and yet another’s parents were daily wage workers in the nearby village. Most of them went to government schools nearby.

The film also features two girls, around 13-years-old, whose parents had begged Uday not to cast them as they wanted to get them married immediately, and being part of such a project would malign their image forever.

“It took weeks to convince girls also and make them comfortable with boys. One of the girls’ mother was an alcoholic and said we are spoiling her daughter’s future, threatening to send her daughter away. I had to call my mother to the village to convince her,” he says.

The director also had to seek protection from the police in order to complete the film.

“There are scenes in the movie involving a brothel, which we set up in nearby villages. The setting and all attracted so much audience and objection to what young boys are being made to do in the set, that we had to seek local police protection to complete the scene,” he says.

Uday’s inspiration to cast people of the village came from another film, Village Rockstars (2017) – an Assamese feature film revolving around a young girl’s journey hoping to become a rock star.

The young director plans to screen his movie in towns and villages of the state in the next few months after the film is released on an OTT platform. Season of Innocence was also selected for the Ahmedabad International Children’s Film Festival in 2020. #HydTravel #hydnews