It is largely unskilled women who roll beedis in Jagtial district of Telangana. The work is physically demanding, wages are poor and it’s a on-going fight for healthcare benefits and fair wages. A Modi-issued identity card promises a lot, but accessing one is not easy.

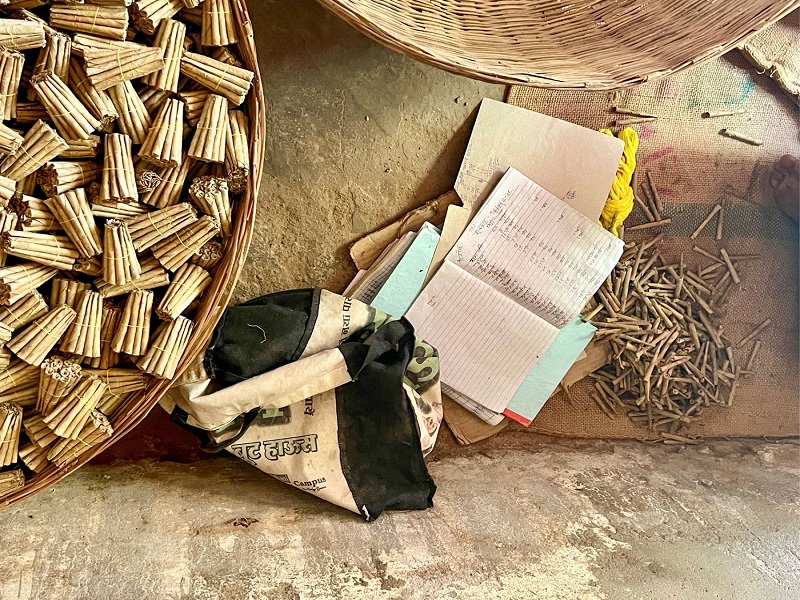

Nisha is seated on the ground, fanning herself. The temperature is rising in the hot June afternoon and the smell of tobacco and dried leaves makes the air heavy. “I could make only so many beedis this week,” she says, showing the roughly 700 beedis wrapped in bundles of 17 each. “They’ll probably be worth less than Rs. 100,” says the 32-year-old beedi maker, talking about her week’s work. A thousand beedis bring in Rs. 150 here in Jagtial district of Telangana.

Every Wednesday and Friday, beedi makers bring the beedis they have made, and also collect raw materials for the next round of rolling. Many factories are located on the outskirts of Jagtial city. They employ thekedars (contractors) who in turn contract the work out to primarily women.

The women will pick up their supply of the raw material and work through the week rolling tendu leaves with cut tobacco and tied with fine threads into neat kattas (bundles) of beedis . They do this work after they are done with the household chores to add to their average monthly household incomes of roughly Rs. 10,000-20,000 which has to feed and sustain families of 8-10 people. Most of the women are agricultural labourers or have small holdings.

“The dry tendu leaves need to be soaked in water till the leaf veins pop out. Then, the leaves are cut into small rectangles using a farma [iron stencil]. Zarda [flavoured tobacco] is added inside and then the leaves are rolled into a beedi ,” explains Nisha. Each must also be fastened with a coloured thread which also acts as a brand indicator, differentiating one company from another.

These are then brought to be sold to the beedi ‘factory’ – essentially a beedi making brand’s processing and packaging unit and storehouse. They hand over their work to contractors who accompany them to the factory or pay them directly. Within the factory, they are sorted, baked, packed and stored.

The beedi makers here are mostly Muslim women but other communities are also engaged in this livelihood.

The roughly 25 factories in Jagtial owe their genesis to the proximity of several tendu forests in the surrounding districts of Kamareddy which has a forest cover of 20 per cent . Aarmoor, Koratla, Banswada, Metpally, Raikal and Dharmapuri are rich sources of tendu leaves – a crucial component in the production of beedis – used as wrappers for the tobacco.

On a warm summer afternoon, dressed in brightly-coloured salwar kameezes , half a dozen women are waiting to get their beedis counted. From the nearby mosque, you can hear the sound of the Friday namaaz over the sound of their chatter and arguments with the thekedar . The women are seated with their taslas (iron wok-like vessels) that hold a week’s work.

Amina is unhappy with the counting: “There were more beedis, but the thekedar rejected them while sorting” she says. The women refer to themselves as beedi mazdoor (labourers) and they say that the price of Rs. 150 for a 1,000 beedis is unfair for the effort.

“I would rather start sewing. That would pay me much more,” says Janu, a former beedi maker. However, when she started, at the age of 14, “I didn’t have much skill or choice,” she says.

The hours of hunching cause severe back and neck problems for the workers, and numbness in the arms, making regular household chores difficult. The women get no compensation or medical aid, the factory owners discounting their difficulties: one of them told this reporter, “women are just sitting at home and rolling beedis,” completely disregarding their work-related ailments.

“They can earn up to 500 rupees a week,” he said, and added that he thought it is a good ‘deal’ for meeting household expenses. However, his estimate of Rs. 500 a week would require a worker to make almost 4,000 beedis – what they currently manage in a month.

All the women we spoke to complained of physical stress and injuries. The continuous rolling of wet leaves and the constant contact with tobacco leads to skin problems as well. “Haath aise kate rehte hain, nishaan tak pad jaate hain [My hands are covered with cuts, sometimes they even leave marks behind],” says one of the workers, holding her hands out for me to see the calluses and blisters of 10 years of working.

Seema, another worker, says she tries to offset the constant exposure to wet leaves by “applying Boroline [a soothing ointment] on my hands before sleeping, or my skin peels off after being exposed to the tobacco and wet leaves.” The 40-year-old adds, “I don’t consume tobacco, but I used to start coughing even at the smell of it.” So around 12-13 years ago, she finally quit and began working as a domestic worker in the city, earning upto Rs. 4,000 a month.

Razia, has been rolling beedi for longer than she can remember. She chides the thekedar who is weighing tendu leaves: “what kind of leaves are you giving us? How will we make good beedis from them? You’ll just end up rejecting all these while checking.”

The monsoon is another worry. “Jo voh barish ke 4 mahine lagte the, mano poori beedi kachre mein jaati thi [During the four months of monsoon, it feels like almost all beedis go in the garbage].” The tobacco, rolled in wet tendu leaf, is unable to dry properly and becomes mouldy, ruining the entire bundle. “We can barely dry our clothes [during the rainy season], but we have to dry those beedis,” or they will not earn.

When a thekedar rejects a beedi, besides the loss of labour time, the money for the raw materials used to make it is also deducted from their earnings. “Khoob lambi line lagti thi ginvaayi ke din. Jaise taise number aata tha, toh tab aadhi beedi toh nikal dete the [There used to be a very long queue for getting the beedis counted. And when our number finally came, the thekedars used to remove half of them],” says Janu, recalling the wait and anxiety.

The beedis are rejected on the basis of several criteria like length, thickness, quality of leaves and rolling. “If the leaves become brittle and tear slightly while rolling, or if the thread is fastened loosely, then the beedis get rejected,” explains a beedi mazdoor in her sixties. The workers say that the thekedars keep the rejected beedis for themselves sell them for a cheaper price. “But we didn’t get any remuneration for it. Neither do we get those rejected beedis back.”

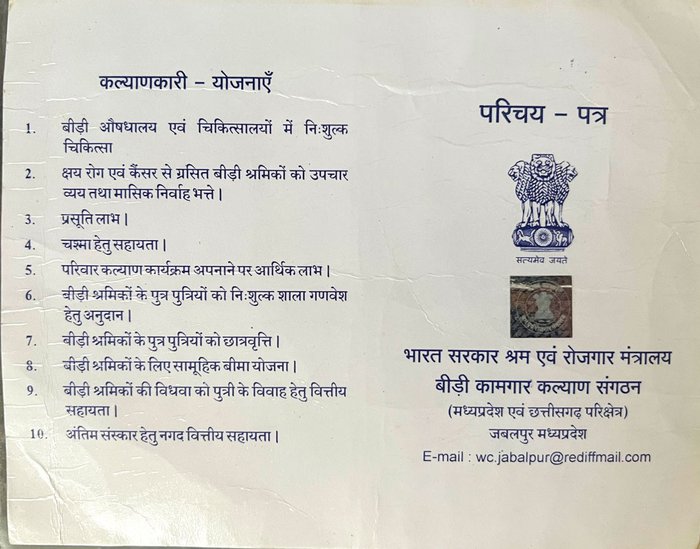

The Modi government started making beedi cards for all those who are engaged in beedi making in 2014 under the The Beedi Workers Welfare Fund Act, 1976 . Although the main purpose of beedi cards is identification of workers, it also enables them to avail several government schemes such as free treatment at government hospitals, childbirth benefits, cash for last rites of deceased, optical checkups and spectacles, scholarships for school-going children, school uniform grants, etc. The Beedi and Cigar Workers (Conditions of Employment) Act, 1966 enables them to avail these benefits. Mostly, the beedi workers who have the card, use it to get free or subsidised medicine from specific dispensaries.

“Zyada kuchh nahi lekin badan dard, bukhaar ki davaai toh mil jati hai [It’s not much, but we at least get basic medicines for body ache, fever],” says Khushboo Raj, a 30-year-old beedi cardholder. She had been rolling for 11 years but left recently to work as a sales assistant at a small bangle store in Karimnagar city.

To avail of the card, “we have to make a few beedis in front of the officer,” says Khushboo, sarkari officer dekhte hain ki humse sahi mein beedi banti bhi hai ya sirf aisehi card banva rahe hain [The government officer checks if we genuinely know how to make beedis or are we just getting a fake card made for benefits],” she adds.

“If we get our card made, they cut funds”, said one woman who had a card in her old village and is wary of pointing fingers at the malpractices. But she did say that the owners cut the money from the workers and use that for the fund. The government also contributes an equal amount to this fund under the 1976 Act . The workers can either withdraw this money under some of the mentioned schemes, or they get the entire deposit back once they stop making beedis for good.

Khushboo received Rs. 3,000 as fund money when she stopped making beedis two months ago. To some workers, this fund system seems beneficial, but to many others, it seems like they are getting even lesser immediate wages for their labour. In addition to this, there is no guarantee that the fund money would be returned to them in the future.

Although the beedi card seems beneficial, the process to get it made is unsupervised and can be exploitative for some. One of them recounted an incident where she had gone to get her beedi card made at the local centre and was sexually harassed by the sahab (officer) there. “He swept his gaze over me and asked me to come the next day. When I went there the next day, I took my younger brother with me. He asked me why I brought my younger brother with me, [he indicated] I should have come alone,” she says.

When she refused to get the card made, he continued pestering her and staring at her. “The other day, as I was passing by that area, he saw me and started calling out to me. He made a scene,” she adds. “Don’t think that I am a gullible woman, I haven’t come here to get involved with your dirty intentions, and if you continue with this, I’ll get you transferred,” she had said. As she recounts the incident, her fists are clenched and her voice is raised. “Bohut himmat lagi thi tab [It took a lot of courage],” she says, “he had done the same thing with 2–3 other women as well, before getting transferred.”

When the women come together to sell their wares, they also joke and laugh, forgetting their aching backs and painful hands as they wait for their turn. The bi-weekly meetings also give them a sense of community.

“All this jest and talk in these meetings…It makes me feel nice and happy. I can get out of the house,” some women told #KLhabarlive.

The air is buzzing with chatter – gossip about the latest family drama, antics of their children or grandchildren and genuine worries about each other’s health are shared. Seema is recounting how her four-year-old grandson got kicked by their cow when he was being a nuisance while his mother was milking the cattle in the morning; another chips in with the latest update of a neighbour’s daughter’s wedding.

But when they leave for their homes, the happy noises die out as concerns about managing the household with very limited earning returns. As the women walk back with their meagre earnings, the trade they make for their labour and their health seems unfair.

Seema recalls the pain and problems she experiences: “Back, hands, arms… everything used to hurt a lot. These fingers that you see used to thin down and become lumpy from rolling beedis .”

Despite their woes and worries, the beedi makers of Telangana continue to toil, trying to sustain themselves on very low wages. As one of them says, “ Ab kya karen, sabki apni majboori hoti hai [What can one do, everyone has their own compulsions].” #hydkhabar