The coveted jewels of the Nizam era will once again be on display at the National Museum in Delhi, after a long gap of 12 years. The exhibition in itself is a spectacle as the fabled Nizam treasure, which is a shining example of Deccan craftsmanship, was relegated to the vaults of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1995, after a prolonged battle for its possession between the government and the erstwhile royal family.

As the national capital is gearing up for the exhibition, Esra, former wife of late Nizam Mukkarram Jha, has once again appealed to the government to bring the jewels back to Hyderabad and make them Deccani showpieces. During the state formation in 2014, KCR had promised Esra to initiate talks on getting the jewels back to the city, but the promises have remained unfulfilled.

Why don’t the jewels, which have historic value, merit a display like the ones in the Tower of London, where even the famed Kohinoor diamond finds a place? In 2002, when Chandrababu Naidu was the Chief Minister of undivided Andhra Pradesh, he is said to have written six letters to the Centre, claiming the state’s stake in displaying the jewels. It was after this that the jewels were brought down to Hyderabad twice for display at the Salar Jung museum. Is safety the only parameter that has made the government lock away the jewels in the vaults of RBI?

How did the jewels reach the RBI vaults?

“Soon after Azam Jah’s death in 1970, the trusts decided to sell the jewellery. This led to a prolonged battle between the trustees and the government of India who didn’t want the jewels to be auctioned as they considered it a part of our national heritage. Finally, in 1995, the Centre won the case and bought the jewellery after paying a sum of Rs 218 crore to the trustees.

Ever since, the jewels have been locked away in the RBI vaults as the government cannot decide where to display them,” explains historian Mohammad Safiullah, also cultural advisor to the Nizam trust.

Usha Balakrishnan, the author of Jewels of the Nizams, an extensive documentation on the collection, says that it’s perhaps the absence of an expert curator, the need to provide so much security and other logistical issues that has put the Centre in a tight spot.

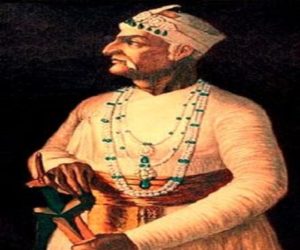

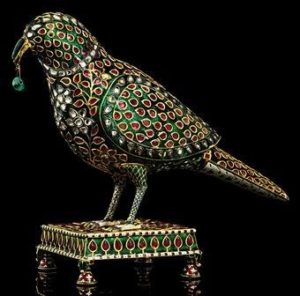

“The Nizam’s jewels are set with the fabulous Golconda diamonds, emeralds from Colombia, rubies and spinels from Burma and Basra pearls. They epitomise Indian aesthetics and design, Indian craftsmanship and the wealth of India. We owe thanks to the wisdom of the seventh Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan, who created the Jewellery Trusts that enabled the government of India to acquire the jewels for the nation.

There have been two temporary exhibitions in Hyderabad, one in 2001 and the other in 2007. But the exhibitions have always rotated between Delhi and Hyderabad. According to Safiullah, the transfer of jewels from the RBI vaults raises a pertinent question: the control of ownership. The Centre fears that once the jewels reach Hyderabad, the state may claim ownership over the treasure.

“The government paid Rs 218 crore way back in 1995. So even if the Centre agrees for a permanent display in the Salar Jung museum, they won’t let go of their control over the collection. The question of ownership has always been a matter of contention in bringing back the jewels to Hyderabad,” Safiullah says.

Though the jewels are currently in the RBI vaults, Usha points out that no matter who owns the jewels, their association with the Deccan cannot be denied.

According to historians, if a proper state of the art infrastructure was created to exhibit the jewels, the government would have earned profits surpassing the Rs 218 crore paid in 1995.

“But what is the incentive for the Centre in displaying the jewels? The jewellery is now worth billions of rupees. The collection consists of the famous Jacob diamond, the seventh largest diamond in the world. By any means, the collection is phenomenal. In Tehran, we have the national museum housing the Iranian jewellery collection or the Tower of London in Britain.

But in India, the question is who will bell the cat?” Safiullah says, adding, “It’s pure lethargy on the part of the Centre to lock the jewellery away for 12 long years. The government fails to realise the boost in tourism a permanent exhibition of this sort will create in our country. All we need are leaders who are willing to take up the task of constructing state of the art infrastructure and provide adequate security.”

But not all historians agree. MA Qayyum, a Hyderabad-based historian, says that a simple research on the cost to display such jewels will provide an answer on why the jewels are locked away from the public eye.

Also, the state which is now crying foul, had made no attempts when the government had bought the jewels in 1995 to make the jewels a state heritage. Considering the present relation the state has with the Centre, it doesn’t seem the jewels will be back in the state anytime soon,” Qayyum opines. #KhabarLive